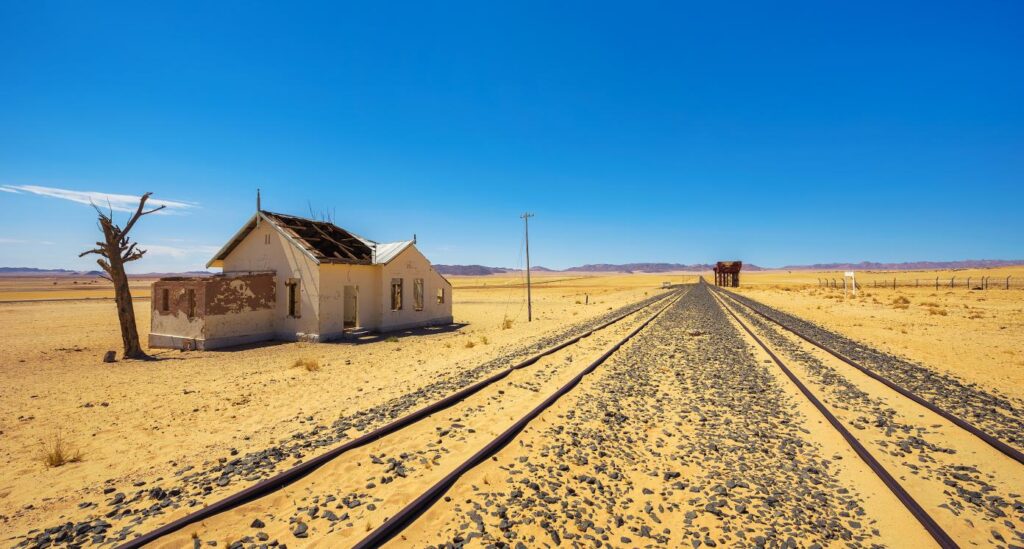

Namibia’s bid to establish itself as a regional logistics hub is being hampered by an underdeveloped rail network, with analysts warning that continued neglect could undermine trade competitiveness.

Simonis Storm junior economist Almandro Jansen said while progress has been made in ports and airports, rail remains the “missing link” in the logistics chain.

“Over the past decade, the government has consistently allocated far larger budgets to roads than rail, funding road maintenance and expansion while the rail sector has been left chronically underfunded,” he said.

Jansen explained that this imbalance has forced cargo onto Namibia’s roads, raising costs and accelerating highway deterioration.

He noted that heavy cargo from Zambia and the Democratic Republic of Congo, which could transit through Walvis Bay by rail, is instead rerouted south.

“Cargo that could transit through Walvis Bay by rail is often rerouted south because Namibia’s network cannot handle the volumes. The missing rail link has become a regional bottleneck,” he said.

Transport statistics underline the reliance on other modes. In June 2025, sea accounted for 56.7% of exports, mostly uranium and fish, air 23.6% driven by gold and diamond exports, and road 19.7%, largely into regional markets. Imports were dominated by road at 60.5%, reflecting dependence on South African corridors.

“By gateway, Walvis Bay port remained the main artery, Hosea Kutako International Airport supported high-value goods, and border posts such as Ariamsvlei and Noordoewer were critical overland entry points. These hubs cannot reach their full potential without a stronger rail backbone,” Jansen added.

He welcomed skills reform initiatives, including the Ministry of Works and Transport’s Namibian Railway Qualification Framework, but warned that training alone is insufficient. “Training reforms will need to be paired with capital investment if rail is to play its intended role. South Africa’s Transnet, which outsourced freight corridors to private operators, offers a model Namibia could consider,” he said.

According to Jansen, private participation in key corridors such as Walvis Bay–Grootfontein, the Otavi–Tsumeb mining belt, and the Ariamsvlei–Lüderitz line could attract funding for track upgrades and locomotives, easing pressure on TransNamib and expanding cargo throughput. “Redirecting even part of the billions allocated to roads into rail modernisation would transform Namibia’s logistics. A stronger rail system would lower transport costs, protect roads from heavy trucks, and boost Walvis Bay’s competitiveness,” he said.

Jansen cautioned that without reform, Namibia’s trade will remain constrained. “Addressing the missing rail link is not just logistics, it is structural trade policy. With reforms, Namibia can rival Durban and Maputo as a Southern African gateway and anchor its trade growth on a more resilient foundation,” he said.

His remarks echo those of Parliamentary Standing Committee Chairperson Iipumbu Shiimi, who recently warned that government’s funding priorities risk undermining its transport hub ambitions.

“16 billion on roads, 4 billion on railways, while the need is actually the other way around. So if you really want to build a transport hub, much of the emphasis must now go to railway,” Shiimi said.

Shiimi added that while roads remain important, Namibia’s outdated railway network—much of which dates back to before the 1960s—requires urgent investment.

He said prioritising projects such as the planned line to Katima Mulilo could deliver significant economic and logistical benefits.