Faced with sticky inflation but sluggish economic growth, the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) is considering changing its interest rate modelling tool.

This is according to Genera Capital investment specialist Professor Adrian Saville.

Saville said there is a considerable debate around the appropriateness of inflation targeting, i.e. using interest rate cuts and hikes to control inflation.

On the one side of the debate is a principle called “monetary disciplineâ€.Â

Proponents of this principle believe South Africa’s inflation should be aggressively and assertively managed through a strict stance on interest rates. In other words, high interest rates keep inflation low.

The SARB leans more towards this side of the debate, having introduced inflation targeting in February 2000. The reserve bank attempts to keep inflation within a target range of 3% to 6% using monetary policy tools like short-term interest rates.

According to the SARB, “The core idea of inflation targeting is that monetary policy has only temporary effects on growth, but permanent effects on prices.â€

The other side argues that this obsession with keeping inflation low comes at the cost of high interest rates that hurt the economy.

Chief economist at Sanlam Investments Arthur Kamp said that the SARB did not cause South Africa’s growth problem.

Instead, the problem reflects failing infrastructure, too much government involvement in economic activity, policy uncertainty, and low business confidence.

However, the country’s sluggish growth and weak currency amidst high inflation places the SARB in a difficult position, as it needs to decide between curbing inflation or providing relief to an ailing economy.

Saville said there is a happy medium – a “truth†– to be found between the two sides of this debate.

Meeting in the middle

Saville explained that inflation is “running in the rearview mirror†rather than something that suddenly appears and disappears when the SARB implements some policy action.

Inflation, and inflation expectations, are challenging to manage. One can see this in markets where inflation is currently close to double digits, such as Europe and North America.

As inflation rises and the public struggles to see an end, inflation becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy as wage increase demands also reach double digits in preparation for higher inflation.

In addition, the instruments at the reserve bank’s disposal to manage inflation – interest rates – are blunt, inexact and have a long lag.

This is why the public must have confidence in the robustness and firmness of its monetary policy authority.

The SARB has been immaculate in this regard, said Saville.

A new model

In its latest Monetary Policy Review, the SARB said its monetary policy decisions would continue to be data-dependent and sensitive to the balance of risks to the outlookâ€.

It also said the monetary policy committee (MPC) would “look through temporary price shocks and focus on potential second-round effects and the risks of de-anchoring inflation expectationsâ€.

Bloomberg reported that changes to the SARB’s model would include the following:

- A mechanism to account for fiscal policy actions in a systematic manner

- Distinguishing between private and public wages

- Augmenting the Phillips curves for the various consumer price index components to include nominal unit labour cost growth, along with the current real unit labour-cost gap

- Accounting for changes in fuel and electricity costs that often spill over into core and food price inflation

- Reflecting the state of the real economy by using the output gap along with a growth gap.

Saville said that the ideal interest rate modelling tool would consider the impact of interest rates on both the nominal and real economy.

The “real economy†refers to investments, economic growth and employment in the country. Regarding the impact of interest rates, the real economy often experiences “spillover†or “second-order†effects rather than a direct impact.

According to Saville, there is little evidence that interest rates influence investments in the country, which the new model should consider.

The nominal side of the economy refers to prices and interest rates. Here, the SARB needs to consider the impact of inflation across the economy and on different income groups.

He said no or low-income earners in South Africa often experience the highest inflation rates.

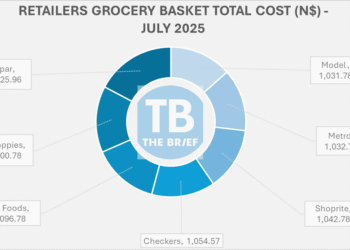

Data from Discover and Visa’s latest spending trends report have backed this up. It showed low-income earners spending 47% more on groceries now than in 2019.

More changes

SARB governor Lesetja Kganyago has recently said they want to adopt a lower inflation target for South Africa.

Currently, the SARB’s target range is 3% to 6%, and it aims to anchor inflation around the mid-point of this range – 4.5%.

At the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington, Kganyago said a 3% inflation target “would help dampen exchange rate volatility and sovereign risk, reduce the potential for upward drift in the real exchange rate, and materially lower debt service costsâ€.

He said this lower target would benefit fiscal policy and stronger growth, adding that structural reforms and key deregulations of transport and electricity are critical in South Africa.Â

“But so too is a shift in fiscal policy back to predictable, transparent rules.†-dailyinvestor